when ray and emma drive up to the san andreas fault, what do they see (look carefully)?

What if I told yous Star Wars and The Godfather were the same story? You'd telephone call me crazy, right? At present what if I said both are essentially the same as Dice Hard? Crazier however? What if I sweetened the pot with Groundhog Day (1993), Cast Away (2000), Donnie Darko (2001), and The forty Year-Old Virgin (2005)?

Completely insane?

So, you're telling me these are not all stories nearly an innocent outsider who gets swept up into a confusing or chaotic state of affairs: who first responds passively or reactively by only trying to suffer and/or allowing other forces or persons to control his fate, decides at the Midpoint to seize command of the situation, and so grows into a far more proactive individual in Human action 2B, and has this transformation fully tested in Human action 3?

Because from that perspective, they are nevertheless.

Marlon Brando as Don Vito Corleone in The Godfather

Now, what if I said Chinatown (1974), Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), and Pixar's WALL-E (2008) were the same? You'd lock me in a nuthouse. That is, until you realize these are all stories about characters who willingly insert themselves into conflicts where they practise not rightfully belong, due to the lure of some mysterious person, object, or state of affairs.

Whether it be Jake Gittes and the Water Department conspiracy, Indiana Jones and the Ark of the Covenant, or WALL-E and EVE, a growing obsession with the lure causes the protagonist to meddle more and more in the exterior conflict, reject to extricate himself when the danger becomes articulate, and ultimately choose to directly face and defeat the opposing forces, all to finally merits the lure.

How nearly When Harry Met Emerge (1989), True Dust (2010), and… oh, say Marvel's The Avengers (2012)? What could they have in common?

Nothing. Except a story where fate brings together two or more strangers of conflicting personalities to form a tentative partnership. The characters offset endeavour to ignore or put up with their incongruities for the sake of harmony, just then find disharmonize when serious flaws surface around the Midpoint. This leads to a temporary break-up. Nonetheless, after developments crusade the characters to recognize the relationship'southward importance, compelling them to reunite and pledge their full loyalty.

Jeff Bridges as Rooster Cogburn in True Dust (2010)

These connections are no mere coincidences. Nor are they rare occurrences. These are simply a few examples of a cinematic phenomenon called Plot Patterns.

Large collections of films which outwardly appear to have nothing in common will in fact share a nearly identical structure of plot. The premise may be different. The genre may be dissimilar. Style, tone, settings, and characters may be unlike. However when all superficial details are stripped abroad, the form of the plot is substantially the same.

How is this possible? Well, i must first remember that structure is almost shape, not content. It is near the nature of events, when they occur, and how they modify the dramatic situation. The literal who, what, where, and why of these events belongs to content—the substance which fills the structural vessel.

Construction and content are largely independent. However, the pliable nature of storytelling allows these ii elements to adapt to ane another – that is, the content can be shaped to fit the needs of the construction, and vice versa – to create the appearance of a face-to-face whole.

As a result, any premise in whatsoever genre may be potentially executed through the same construction of plot. Since viewers focus on a story's content and rarely if ever the construction underneath, the structural similarities between films get continually unnoticed – by everyone, often including the storytellers who create them.

Bruce Willis as John McClane in Die Hard

In 2012, I began what would become an intensive study of over three hundred critically- and commercially-successful American films. Though these films ranged from one-time classics to recent releases and covered all available styles and genres, I was shocked to discover how nearly every case followed i of sixteen general patterns of plot.

Further investigation revealed almost of these patterns could exist split into 2 or more subtypes in which the structure becomes so specific that films come up to mirror one another on a near plot betoken by plot signal ground.

Currently, my count of these patterns and subtypes stands at xxx-iv. At that place are probable fifty-fifty more. However, any additional patterns occur then infrequently that none were encountered in my pool of over iii hundred films. (Though it may seem similar a bit of a tease, there is no room in a single article to explain every 1 of these xxx-four patterns. Detailed breakdowns can be institute in my book Screenwriting and The Unified Theory of Narrative, Part Two: Genre, Pattern & The Concept of Total Meaning.)

Yet, the most surprising affair almost these discoveries was the fact that films which shared identical structures ofttimes diameter no resemblance to one another in terms of style, genre, or type of dramatic activeness. Comedies stood side-by-side with psychological thrillers; fast-paced activeness with intimate character pieces; popcorn blockbusters with Oscar recipients.

If y'all would similar more examples, Spider-Human being (2002) follows the same structure equally The Graduate (1967); Apocalypse Now (1979) the aforementioned equally Little Miss Sunshine (2006); Martin Scorsese'south The Departed (2006) the same as the Farrelly Brothers' There'south Something Almost Mary (1998). I could become on and on.

Piddling Miss Sunshine

Yet despite their superficial differences, these films followed the same rising and fall of events, only in such diverse contexts that their affinities were virtually unrecognizable.

Because of such contrasts from movie to film, I find it hard to believe these collections could take found their identical structures through witting will or fake. Though Hollywood is known for its reliance on formula and habit of copying previous successes, farthermost differences in premise, genre, characters, and so along make it absurd to suggest that Dice Hard (for instance) was a direct attempt to copy the plot of Star Wars or The Godfather. Or that Chinatown, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and WALL-E were all modeled on the same formula.

These stories conspicuously developed separately from i another – yet somehow gravitated toward the same plot structure by their own accord. This is the essence of a pattern.

Formulas are intentional. They are applied from the offset of creation to achieve a planned result.

Patterns, on the other manus, are spontaneous and naturally-occurring. They are a consequence, not a cause. Our world is filled with naturally-occurring patterns, found in everything from geology to social trends. There is nothing magical about these patterns. Nor practise they come well-nigh by any intentional plan. Patterns simply exist because multiple carve up instances react in the same ways to similar factors of environs.

Yet if plot patterns have formed through a samesuch process, what factors of environment could cause dozens, even hundreds of films – separated past both place and time – created by dissimilar artists on unlike subject matters – to continually conform to the same arrangements of plot?

That'due south complicated.

How does this occur without the storyteller'south knowledge?

That's also complicated.

But I will give you a hint. Don't look any strange films to fit into my listing of thirty-four common patterns. This collection is exclusive to the American cinema alone. Why? Because every globe cinema creates its own plot patterns. While some may announced similar to American varieties, virtually contain clear differences or are entirely unique to their land of origin. This suggests the origin of plot pattern is cultural. More specifically, each plot pattern acts equally a dramatic expression of i or more than of its culture's core principles of belief.

Michelle Yeoh as Yu Shu Lien in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

Core principles of belief are themselves a heady topic. It must and so suffice to say that core principles are the most basic values, ideas, and concepts of conventionalities at the foundation of cultural identities.

As the inarguable "truths" of each civilisation, core principles give the people a mutual frame of mind through which they may view the world and evaluate all things. Storytellers who occupy the same culture will share many, if not all, of the aforementioned cadre principles of belief. Thus, acting individually, a culture's many storytellers volition continually create narratives which explore or endorse the same ideas or behavior once again and again.

While these stories may follow different paths in terms of dramatic content, or focus on endless specific areas of concern, they all develop and resolve their conflicts according to the aforementioned concepts of "truth." In other words, these many stories continually point back to the same core beliefs to state *this* is true, and *this* is how people should behave.

Shar Rukh Khan every bit Om Prakash Makhija / Om Kapoor in Om Shanti Om

Yet this in itself does non explain the highly specific patterns of plot found in our world cinemas. For while many storytellers may base their works on the aforementioned idea or belief, the general art of storytelling allows for a multitude of forms and methods to limited such things.

Nevertheless, such possibilities come across significant restrictions in the feature-length film. Different other story mediums such as the novel, the cinema's unique qualities and limitations force narrative discourse into much tighter boundaries. Examples include the cinema's dependency upon audio/visual communication, the necessity of dramatic conflict, and the characteristic film's surprisingly limited 90-150 minute length.

Because of these impositions, cinematic stories must be tailored to fit their concrete environment. Some forms and structures are far more than effective than others. Some methods engage the audience more strongly or communicate more conspicuously. Indeed, the entire field of screencraft can be considered a search for the all-time ways to match story material to the cinematic medium.

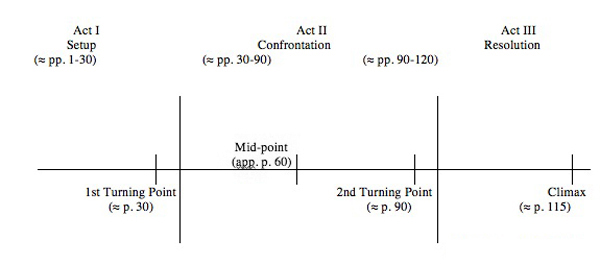

This explains the e'er-nowadays support for the tried-and-true 3-Act structure. Thousands of examples have proven this structure to exist an effective manner to tell a 90-150 minute story within the confines of cinematic discourse.

If we take this one step farther, we may suggest that for every idea or belief, there exists an platonic method to limited it through the feature-length cinematic course. In other words, out of all possible arrangements of plot and grapheme, ane will evangelize the underlying message in the clearest and most dramatic manner.

Every attempt at screenwriting is a search for this most effective arrangement—and in the case of plot patterns, storytellers find it.

Every bit it turns out, there is nothing cosmic about plot patterns. They are not rooted in some Jungian concept of a collective consciousness or anything of the sort. They are merely the effect of ideological repetition met with an unchanging narrative form.

Because cadre principles of conventionalities concur such importance to every civilization, storytellers volition create narratives upon the same principles again and again. Since the factors of the cinematic surround never alter, the "perfect" ways to express these principles through plot and character never change either.

The nigh skilled of screenwriters discover these perfect arrangements – non intentionally, merely in the elementary effort to tell the best possible story. Many agreeing screenwriters follow suit, and – if they are as skilled – find the aforementioned platonic structures through their own accord.

Plot patterns can thus be considered perfect narrative archetypes, each tailored effectually a detail core principle of belief. They occur so ofttimes but because storytellers routinely utilize the same cultural beliefs to address their stories' issues.

While every individual story may make dissimilar choices in terms of premise, genre, mode, or tone, their narratives inevitably gravitate towards these archetypes but because such arrangements prove fourth dimension and once more to exist the most effective ways to communicate ideological messages through the cinema's particular properties of plot and character.

Steve Carell as Andy Stitzer and Catherine Keener as Trish in The twoscore Year-Old Virgin

In determination, plot patterns can exist truly considered a naturally-occurring narrative miracle. Like patterns plant in nature, plot patterns have non formed intentionally. Instead, they are the result of many separate instances responding in similar ways to the same repeated factors of environment.

Do all American films attach to one of my xxx-four plot patterns?

No, they do not.

Practise all successful films? (By successful, I mean that the film fares well both critically and commercially.)

All signs point to aye.

I have found that the most highly-revered of films (titles such every bit The Godfather, Chinatown, Citizen Kane, or Casablanca) follow their patterns nigh closely. The weaknesses of lesser films tin can often exist traced to points where they devious from their designated pattern.

In further dissimilarity, films which lack any clear blueprint usually do poorly. Adherence to a plot pattern certainly does not guarantee success – a film may notwithstanding neglect for many other reasons. But with the exception of nontraditional films which utilise alternative or experimental structures, the bear witness strongly indicates that plot patterns serve a definite office in a film's ultimate audience response.

Orson Welles as Charles Foster Kane in Citizen Kane

Of course, this all provokes additional questions. Why do audiences reply so strongly to plot patterns? What are the 30-4 common plot patterns of American cinema? What core principles practise they limited and how to practise they practice information technology? Why does American movie theater follow these patterns and not others? How exercise they compare to the patterns of other world cinemas?

This is certainly too much to delve into here – and dare I say, even more than than I tin conclusively relate. For though I dedicate much of Screenwriting and The Unified Theory to the details of the plot design miracle, I admit it remains an absolute newborn in the field of narrative theory, and thus may require many years of investigation.

All the same, it seems quite clear that such discoveries concur a greater use and significance far outside the tiny realm of screencraft. Past revealing connections betwixt narrative and civilization, plot patterns may be used to understand our societies, how they evaluate problems, and the way they promote ideas and beliefs. Thus by examining cinematic narratives, we may ameliorate grasp the ideological structures of the worlds in which we live; and in turn, create stories which more adequately serve our social and cultural needs.

[addtoany]

Before Yous Go

Source: https://www.creativescreenwriting.com/patterns/

0 Response to "when ray and emma drive up to the san andreas fault, what do they see (look carefully)?"

Post a Comment